Mrs.

Stevens (Maxine Audley) to Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm) in Peeping Tom (1960)

“Well,

let’s get the wrong people in as well as the right ones.”

Michael

Powell on marketing Peeping Tom

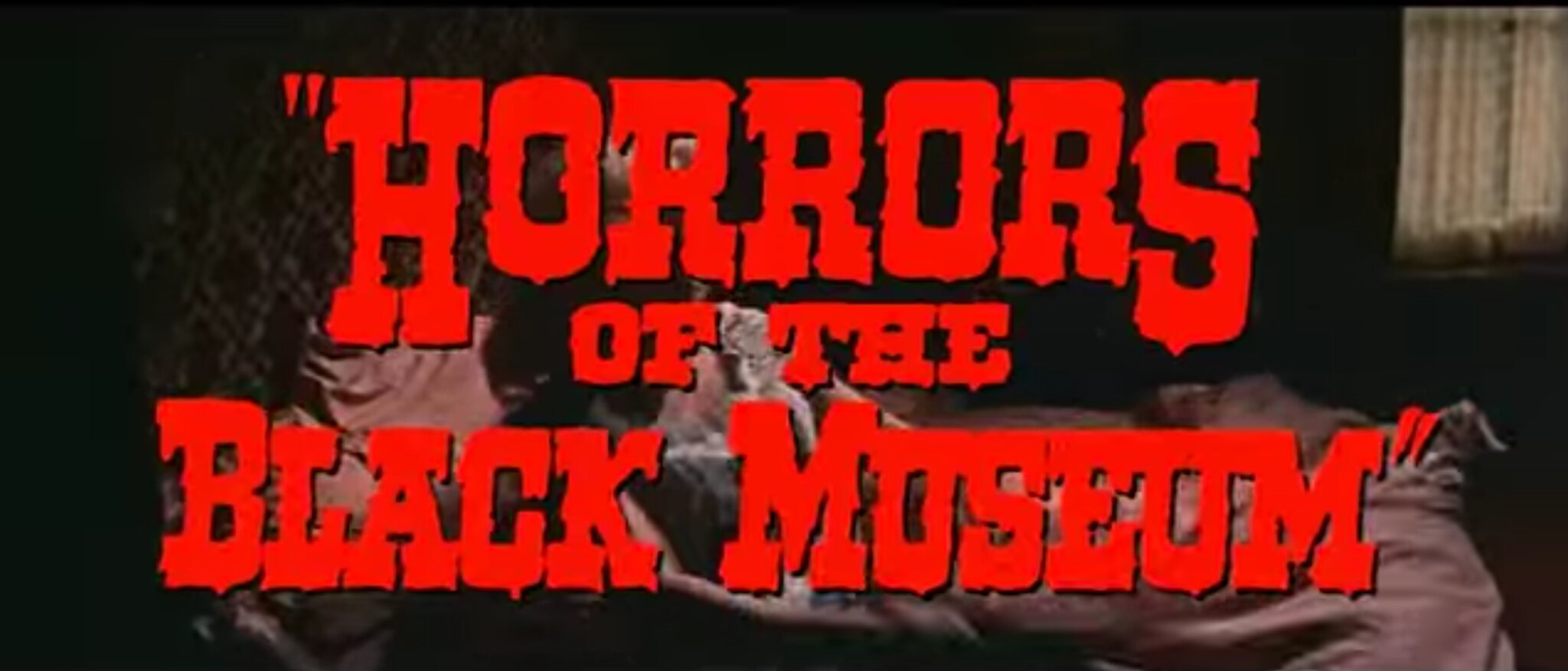

One of the most famous scandals in the history of British cinema is the 1960 release of Michael Powell's Peeping Tom by British distributor Anglo-Amalgamated, a company then enjoying box-office success with the "saucy" (i.e., puerile) Carry On comedy series and violent, pulpy horror films such as Horrors of the Black Museum (1959). Peeping Tom tells the story of Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm), a voyeur and psychotic, whose now-deceased scientist father had subjected him to sadistic experiments as a child, including filming and taping his grimaces and cries of fear while torturing him with reptiles and sudden noises in the middle of the night. As an adult, Mark works as a focus puller in a film studio by day, moonlights taking pornographic pictures, and prowls the street at night with a hidden camera, murdering women with a bayonet affixed to his tripod while he films their faces in final agony. We later discover that the women are forced to watch their own dying faces in a mirror attached to the camera. His first two victims are Dora (Brenda Bruce) a street-based sex worker, and Vivian (Moira Shearer), an extra at the film studio.

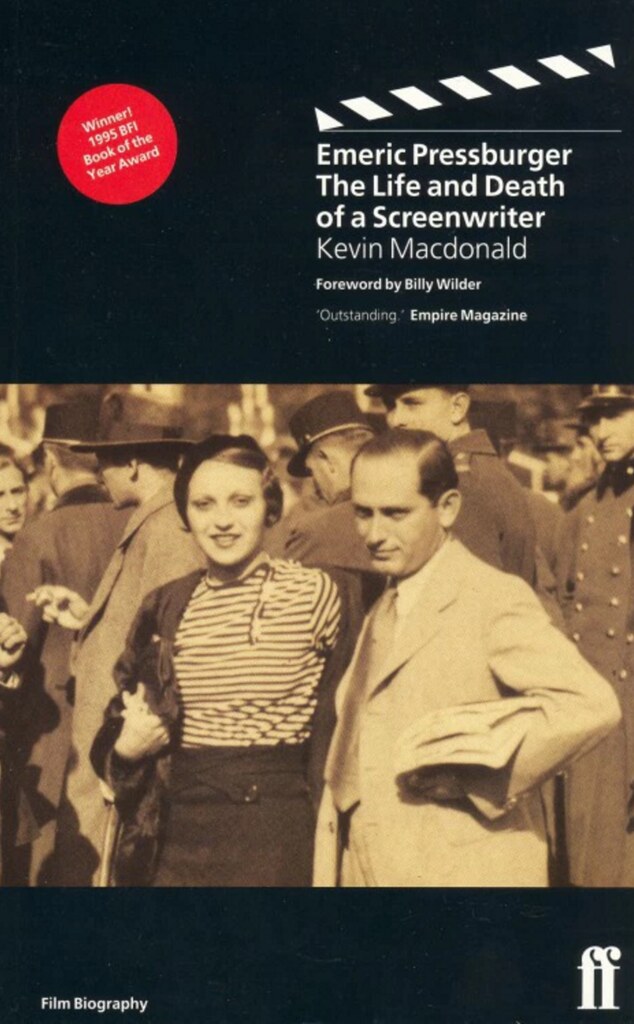

Histories of this greatest of cursed films have emphasized its supposed career-ending effect on director Michael Powell who, two years prior to signing on with Anglo had broken with his longtime Archers collaborator Emeric Pressburger and was no longer supported by the powerful Rank Organization, under whose auspices the team had produced international box-office hits such as The Thief of Baghdad (1940), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947), The Red Shoes (1948), and Tales of Hoffman (1951).

Other histories of the film emphasize the intricate linguistic and psychoanalytic subtext of the film’s screenplay by former wartime code breaker Leo Marks. In these various accounts, Powell and Marks cagily used the resources of Anglo Amalgamated schlockmeisters Nat Cohen and Stuart Levy to produce a subversive, avant-garde film masquerading as a horror programmer which was decades ahead of its time and which was immediately pulled from release after public indifference and excoriating reviews. The film then languished in obscurity until later critics such as Carlos Clarens and director Martin Scorsese, sensitive to its profound philosophical engagement with the deep structures of the horror genre and the institution of cinema itself, pressed for its radical re-evaluation.

If we move the genuinely heroic figures of Powell, Marks, Clarens, and Scorsese to the side and examine the film against the background of distribution and exhibition, a more complex picture emerges. Peeping Tom's director, its British distributor, and the theaters which would ultimately book the film were all responding to a severe crisis in the postwar British film industry which changed the relationship between the production, distribution, and exhibition branches of the movie business. Amidst Britain's decimated 1950s economy, Hollywood was attempting to compensate for its diminishing domestic box office in the wake of suburbanization, the rise of television, and the sale of the major studios' theater chains under the U.S. Supreme Court's 1948 Paramount decision by aggressively promoting its product in British cinemas through its own long-established distribution subsidiaries. This had the catastrophic effect of funneling large amounts of hard currency out of Britain’s devastated postwar economy. The years 1947 and 1948 saw Britain impose a currency freeze and Hollywood retaliate with an export ban. At the same time, the major exhibition circuits ABC, Odeon, and Gaumont extended their first runs of the premiere product of both Hollywood and Britain, leading to a product shortage in provincial and subsequent-run theaters at least as acute as the one faced by American exhibitors during the same period. In the 1950s, cinemas outside of the first-and-second-run markets also struggled to fill thirty per cent of their playdates with British films under the screen quota provisions of the revised Cinematograph Films Act.

It was in 1949, during the darkest days of this fallow period that British distributor Exclusive incorporated Hammer Film Productions to make quota-filling program pictures for the starving British theatrical market. The following year saw the establishment of the British Film Finance Company, a pool for domestic film production funded by a voluntary tax on each cinema ticket sold in Britain, the so-called “Eady Levy.”

When the Levy became mandatory in 1956, Hollywood realized that it could establish nominally “British” production subsidiaries and have its investment augmented by as much as fifty per cent with funds from the BFFC. British producers such as Hammer and Anglo-Amalgamated, and later Compton, Amicus, and Tigon, could have the lion’s share of their own investment in their production slate paid for with Eady funds.

Mark struggles against his compulsion and takes the first, halting steps toward friendship and romance with his downstairs tenant, Helen Stephens (Anna Massey), in spite of the objections of her sightless mother (Maxine Audley), who finds Mark secretive and stealthy. After murdering pin-up model Milly (Pamela Green) during a photo shoot, Mark returns home to find that Helen has discovered his secret home theater and his homemade murder movies. As the police frantically attempt to break down the door to his studio, Mark commits suicide in front of Helen with his own weapon as pre-set still cameras record his death throes. The film ends with a shot of Mark’s now-dark movie screen, while on the soundtrack we hear a taped exchange between the child Mark and his father which ends with the child’s tremulous, “Good night, Daddy. Hold my hand.”

|

| Powell (left) with Emeric Pressburger |

|

| The hallucinatory masterpiece Black Narcissus (1947) |

|

| Moira Shearer in The Red Shoes (1948) |

Other histories of the film emphasize the intricate linguistic and psychoanalytic subtext of the film’s screenplay by former wartime code breaker Leo Marks. In these various accounts, Powell and Marks cagily used the resources of Anglo Amalgamated schlockmeisters Nat Cohen and Stuart Levy to produce a subversive, avant-garde film masquerading as a horror programmer which was decades ahead of its time and which was immediately pulled from release after public indifference and excoriating reviews. The film then languished in obscurity until later critics such as Carlos Clarens and director Martin Scorsese, sensitive to its profound philosophical engagement with the deep structures of the horror genre and the institution of cinema itself, pressed for its radical re-evaluation.

If we move the genuinely heroic figures of Powell, Marks, Clarens, and Scorsese to the side and examine the film against the background of distribution and exhibition, a more complex picture emerges. Peeping Tom's director, its British distributor, and the theaters which would ultimately book the film were all responding to a severe crisis in the postwar British film industry which changed the relationship between the production, distribution, and exhibition branches of the movie business. Amidst Britain's decimated 1950s economy, Hollywood was attempting to compensate for its diminishing domestic box office in the wake of suburbanization, the rise of television, and the sale of the major studios' theater chains under the U.S. Supreme Court's 1948 Paramount decision by aggressively promoting its product in British cinemas through its own long-established distribution subsidiaries. This had the catastrophic effect of funneling large amounts of hard currency out of Britain’s devastated postwar economy. The years 1947 and 1948 saw Britain impose a currency freeze and Hollywood retaliate with an export ban. At the same time, the major exhibition circuits ABC, Odeon, and Gaumont extended their first runs of the premiere product of both Hollywood and Britain, leading to a product shortage in provincial and subsequent-run theaters at least as acute as the one faced by American exhibitors during the same period. In the 1950s, cinemas outside of the first-and-second-run markets also struggled to fill thirty per cent of their playdates with British films under the screen quota provisions of the revised Cinematograph Films Act.

It was in 1949, during the darkest days of this fallow period that British distributor Exclusive incorporated Hammer Film Productions to make quota-filling program pictures for the starving British theatrical market. The following year saw the establishment of the British Film Finance Company, a pool for domestic film production funded by a voluntary tax on each cinema ticket sold in Britain, the so-called “Eady Levy.”

When the Levy became mandatory in 1956, Hollywood realized that it could establish nominally “British” production subsidiaries and have its investment augmented by as much as fifty per cent with funds from the BFFC. British producers such as Hammer and Anglo-Amalgamated, and later Compton, Amicus, and Tigon, could have the lion’s share of their own investment in their production slate paid for with Eady funds.

Anglo-Amalgamated, like Exclusive, was independent of

the vertically-integrated Rank and ABC groups and had been formed in 1949 to

supply quota features to a wide range of exhibitors. Anglo enjoyed after 1958 a

reciprocal distribution arrangement with U.S. low-budget genre film specialist American International Pictures, with each handling the other’s

product line in their home country. A number of Anglo’s horror, comedy, and

crime pictures were financed with a combination of Eady and AIP money,

beginning with Cat Girl in 1957. Thus, we can see that two of the

signature postwar exemplars of the English-language horror cinema—the

black-and-white drive-in program pictures of AIP such as I Was a Teenage

Werewolf (1957) and the colorful Gothic cinema of Hammer films which began

with Curse of Frankenstein that same year—grew out of the changing relationship between the distribution and

exhibition branches of the film industry in both the U.S. and Britain and the two decades-long

product shortage which resulted from these changes.

By the late 1950s, both American and British subsequent-run exhibitors came to rely on an eclectic programming strategy to maintain their twice-weekly program changes, and smaller distributors began to acquire a number of films from continental Europe to release to these product-hungry theaters. Some American companies, such as Mayer-Burstyn, Janus Films, Times Films, and Films Around the World carefully built up an upscale older, educated “lost audience” through their handling of postwar art films. Many of these companies also handled exploitation films under their own moniker or that of a subsidiary. The American leader in this release strategy was Joseph Levine’s Embassy Pictures, which

released horror films such as Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1955) and Jack the Ripper (1959), dozens of dubbed sword and sandal epics such as David and Goliath (1960) and Hercules in the Vale of Woe (1961), and art-house classics like Two Women (1960), Sky Above, Mud Below (1962), 8 ½, and Contempt (both 1963), all of which were promoted on their real, imagined, or added sensational content. During this period, the instability of the categories of art-cinema, horror films, exploitation, and x-certificate sex films was a feature of both booking patterns of films into product-starved theaters and textual elements of the films themselves.

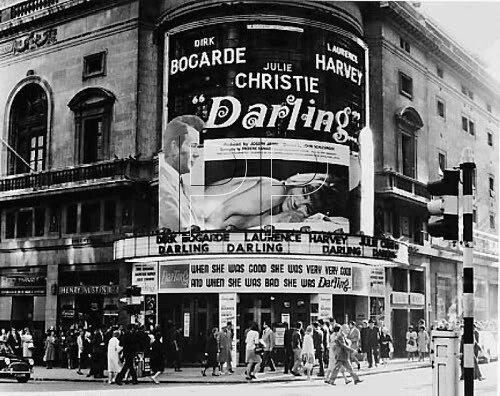

|

| The Plaza in Picadilly Circus |

|

| The ABC Kingston-Upon-Thames |

|

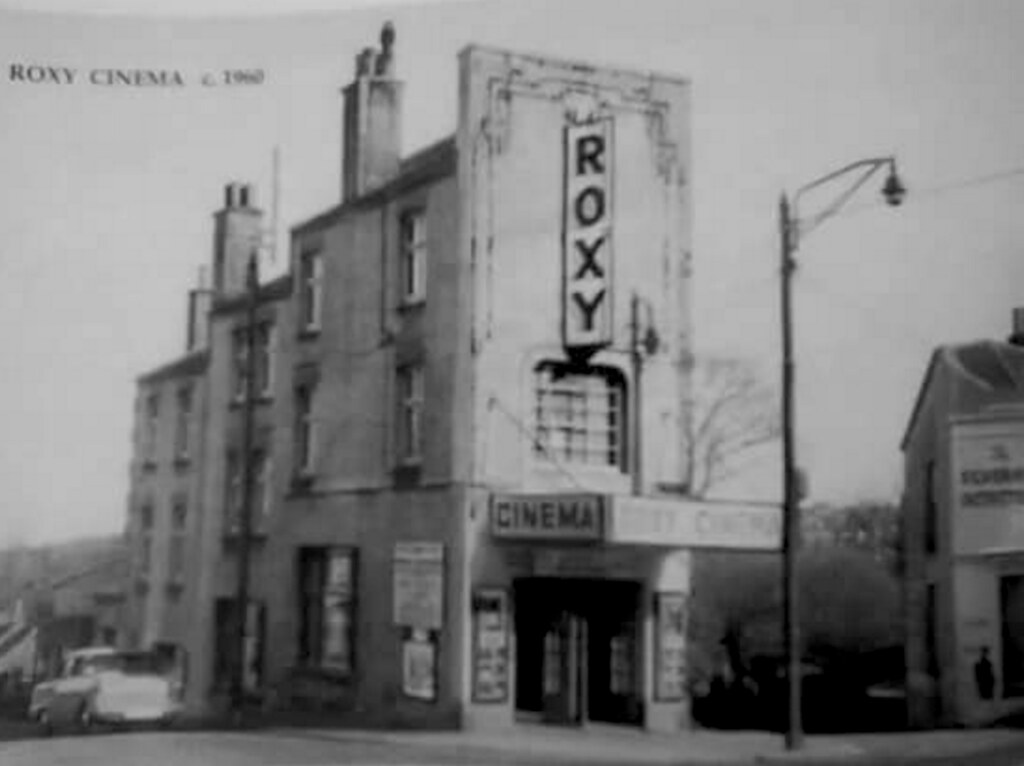

| The Roxy Cinema in St. Leonards |

|

| The theatrical trailer for Horrors of the Black Museum deliberately underscored the film's X-certificate content by ceremoniously refusing to show any of it |

Although many

X-certificate films in a variety of genres enjoyed successful circuit bookings

throughout this period, some producers submitted to cuts to obtain the A rating

and thus an easier circuit release for their films, particularly in theaters owned and controlled by the Rank Organisation, but at

a trade meeting of the Cinematograph Exhibitors Association, local exhibitor

Jim Poole confessed, “I run both the good X films and the bad ones. . . If the

producers will give us something to replace this type of product, we’ll be glad

to show it. Without X films what are exhibitors going to show?” Throughout 1958-1960, several solutions to the quandary of X films and the

desperate and varied programming strategies of the independent exhibitor were

proposed, including a return to the “H” certificate for horror films and the introduction of a new “AA” category for adult-themed films which did

not merit the age restriction of the X certificate. The latter was formally adopted in 1970.

|

| Jacey Cinema chain founder Joseph Cohen (i) with Gala Royal manager Kenneth Rive (r) |

and exploitation movies such as the Italian horror film I Vampiri (1958), the German JD drama Teenage Wolf Pack (1958), and a 1958 double feature of the decades-old American nudist picture Elysia (1934) and the 1956 Japanese taiyozoku “sun tribe” film Crazed Fruit (dubbed and trimmed to barely an hour under the new title, Juvenile Passion). The nudist film trend in 1958-62 was able to take advantage of reclassification of nudist films by the BBFC as suitable for an A rating as long as nudity was featured “in a documentary way. . . [and not] in an erotic setting.” After this reclassification, a major hit in both ABC houses and non-circuit bookings in the provinces was The Nudist Story (1960), which was handled by Eros Films, another specialist in imports, quota program features, youth pics, and X-certificate horror films such as The Trollenberg Terror (whose later American release title, The Crawling Eye, is the source of this blog's name) and Fiend Without a Face (both 1958). Even Anglo-Amalgamated, the largest and most successful independent distributor in Britain, weighed in with a nudist double feature, Nudist Paradise and Liane, Jungle Goddess (1959) which was a huge hit in both West End and industrial bookings.

|

| In 1959, Anglo's nudist double feature had a successful run at the Gala Royal and other theaters in the Jacey Cinema circuit. |

The power of the major theater circuits, the severe distribution drought, the multiform programming strategies of exhibitors and distributors, and the perplexing fluidity of genres all come together in the saga of Peeping Tom. Anglo produced and released Peeping Tom in the 1959-60 season, a time in which the company was scoring big on the ABC circuit with both Horrors of the Black Museum and Carry On Nurse, the second in the long-running comedy series.

The marquee

name of Michael Powell was ideally suited to convince the ABC circuit and its

suburban first-run audiences of the film’s box office potential, since Powell and Pressburger’s features had scored consistently

for over a decade in arch-rival Rank’s Odeon and Gaumont chains. This

impression was abetted by Powell himself, who described the upcoming production

as a “Freudian thriller,” and announced straight-faced to the press that “I think you will find that it

has many points in common with The Red Shoes,” not the least of which

was the casting of Moira Shearer, the former teenage ballerina from the earlier

Archers hit, in a minor role as a bit player at “Shepperfield Studios.” While Peeping Tom was before the cameras at Pinewood, Powell asserted

that

the stylized color by cinematographer Otto Heller and the

meticulously rehearsed and well-crafted performance by leading actor Carl Boehm and the rest of the cast would mute the horrific elements of the story. “It is not a gruesome picture,”

Powell told trade journalist Bill Edwards. “How could I have got such a good

cast (Moira Shearer, Anna Massey, Maxine Audley) if it was?” Edwards must have

missed the memo from studio heads Cohen and Levy, because he referred to Peeping

Tom as a “prestige picture,” albeit one with a five-week shooting schedule,

an ostensible shooting ratio of 1.5 to 1, and extensive use of the Pinewood

film studio itself as a “ready-made set.” Eventually, the budget of the film was slashed in half from the figure touted in trade ads to approximately one hundred thousand pounds.

|

| Powell with his son Columba, who plays the young Mark, on the set of Peeping Tom |

|

| Stylized color and well-crafted performance: Maxine Audley and Anna Massey |

|

| A ready-made film set: The doomed Vivian enters the studio |

|

| Sexualized gore and a cast from the Continent: Anton Differing and Vanda Hudson in Anglo's Circus of Horrors (1960) |

|

| 1961 Kamera calendar featuring Green |

|

| Mark directs Milly in Peeping Tom. Green designed and built the set in which she is posing for a layout in Kamera |

From this

perspective, the wildly dissonant registers of Peeping Tom’s tonal and

generic elements, which generations of critics have perceptively ascribed to a

self-conscious alienating effect designed to bare and reveal cinema’s

underlying sexual economy, are as much a product of

the movie’s prospective distribution and exhibition demands as they are a result of Brechtian design. To be sure, Peeping Tom was crafted as a scalding satire

of the British film industry by a director who was already a

casualty of the changing movie business, with the prestige star-driven cinema

of the Rank empire no where in sight. In the film's sexual and representational economy, “legitimate” studio filmmaking (portrayed here as the rushed production of quota quickies which are literally made up on the spot) shades into the

private “views” shot by Mark within the film, the filmed sadistic psychological

experiments inflicted upon him as a child, and the secret murder movies Mark screens

in his private theater. This array of modes of exploiting film and photography,

each heavily coded by gender, social class, and cultural capital, finds its parallel in

the different stages of Peeping Tom’s theatrical playoff, which included

a widely-promoted West End premiere, a national booking on the ABC circuit in

May similar to other X-certificate horror pictures, hundreds of summer

engagements in nine-penny theaters in the industrial North (where nudist

pictures, exploitation films, and quota programmers flourished), and markets

abroad including the Continent and the U.S.

As we now know, Anglo's promoting of the film's more upscale elements was a catastrophic failure. The use of the names Michael Powell and Moira

Shearer featured prominently in the lead up to Peeping Tom’s West End

premiere, and Anglo hyped its “intensely dramatic and intriguing thriller” by placing an interview with Shearer and an excerpt from the film on the BBC

television program Picture Parade In conjunction with theater owners, Anglo also provided a five-installment serialization of Peeping Tom

for local newspapers, a strategy characteristic of high-profile studio releases. When the film premiered at the Plaza Theater on April 7 for a two-week engagement, on hand were studio heads Cohen and Levy,

director Powell, and stars Carl Boehm, Moira Shearer, Anna Massey, and Pamela

Green.

Massey and Green recall the chilly reception they received from industry

colleagues and members of the trade press at the premiere, and the critical

response was swift and savage. Most famously, Leonard Moseley of Daily

Express confessed that “neither the hopeless leper colonies of East

Pakistan. . . nor the gutters of Calcutta—has left me with such a feeling of

nausea and depression as I got this week sitting through a new British film

called Peeping Tom." Nina Hibben of the Daily Worker opined that “from its slumbering, mildly

salacious beginning, to its sadomasochistic and depraved climax, it is wholly

evil,” and Derek Hill of the Tribune suggested that “the only way to

dispose of Peeping Tom would be to shovel it up and flush it swiftly

down the nearest sewer. Even then the stench would remain." Many of the negative reviews struggled to categorize the

admittedly skillfully-made film which avoided the supernatural and gothic

horror-film clichés easily “dismissed as risible” and which deftly engaged audiences emotionally in the inner lives of its

characters. Isabel Quigly in the Times was angered and bewildered by the

film’s juxtaposition of violent paraphilia with finely-crafted performances,

moody longeurs, and psychological depth. Trade sources, on the other hand, correctly predicted that its exploitable

angles, vivid use of color, and excellent acting performances would help it “do

very well as an X certificate booking,” and a fortnight later, columnist Josh Billings noted that “a savagely hostile

press didn’t prevent Peeping Tom from scoring steadily during its two

weeks stay at the Plaza.”

|

| Anglo's Stuart Levy and Nat Cohen with Carl Boehm and Pamela Green at Peeping Tom's premiere at the Plaza on April 7, 1960 |

Much of the

received wisdom of Peeping Tom’s “cursed film” status comes from its

abbreviated run on the ABC circuit, which began on May 23. Derek Hill’s

jeremiad against the film ended with an entreaty to suburban audiences to avoid

the film’s circuit release once Peeping Tom’s West End engagement came

to an end. In fact, the film “opened to huge figures” in pre-release engagements in Bristol, Bath, Leicester, Doncaster, and other locations “in spite of, or

because of, its extraordinary press reception,” and was described by Billings on the eve of its circuit release as “the answer

to every live showman’s prayer.” But two years of controversy about lobby displays, posters, horror films,

nudist films released with the A-certificate, exploitation pictures carrying

the X-certificate, and nudie magazines such as Kamera, as well as the Anglo

release’s “titillating title” had laid a trap for the film which local

constabularies and watch committees were only too eager to spring. The Reading

watch committee banned the film from chain houses under its authority based

solely on the synopsis in Anglo’s press kit and “the reviews [they] read in

responsible newspapers and journals which criticized the film.” The same thing happened in other

localities, and despite the film’s “clicking” in many engagements, the ABC chain (unlike

subsequent-run and industrial theaters who had to scramble for commercially viable product to book) removed Peeping Tom from its program after a week. This is the source of

the legend that the film was quickly “yanked from distribution” and consigned

to oblivion.

But on June 9, Anglo returned Peeping Tom to the West End for an engagement at the Gala Royal theater at Marble Arch. This West End re-booking of Peeping Tom existed alongside other downtown summer bookings from Gala’s distribution arm which included Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), Le Testament d’Orphée (1959), the 1958 French import Péché de jeunesse aka Sins of Youth (“The Fire of Heaven is in Their Bodies, But The Parents See Only the Flames of Hell!”) For Peeping Tom's Gala Royal run, manager Kenneth Rive festooned the theater’s front with signs quoting the most damning critical assessments of the film, including those by Moseley, Hibben, and Hill, and once again, long queues for Peeping Tom were seen in the West End.

But on June 9, Anglo returned Peeping Tom to the West End for an engagement at the Gala Royal theater at Marble Arch. This West End re-booking of Peeping Tom existed alongside other downtown summer bookings from Gala’s distribution arm which included Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), Le Testament d’Orphée (1959), the 1958 French import Péché de jeunesse aka Sins of Youth (“The Fire of Heaven is in Their Bodies, But The Parents See Only the Flames of Hell!”) For Peeping Tom's Gala Royal run, manager Kenneth Rive festooned the theater’s front with signs quoting the most damning critical assessments of the film, including those by Moseley, Hibben, and Hill, and once again, long queues for Peeping Tom were seen in the West End.

|

| Jacey's Cinephone Theatre on Bristol Street in Birmingham enjoyed a successful run of Peeping Tom in the summer of 1960 |

This was not

unanticipated: in the middle of the film’s

vituperative press reception during the Plaza engagement, Josh Billings

asserted that “its time will come later." The Gala Royal engagement marked the beginning of Peeping Tom’s

successful release in smaller provincial houses which were suspicious of “prestige” films designed exclusively for West End audiences

and who still needed Anglo features in commercial genres. During this phase of the film’s playoff, Powell’s name was seen less than that

of “Kamera girl” Green, who noted

in retrospect that “for most of the

publicity purposes, my pictures were used as there seemed to be hardly anything

available from the publicity department." Although

removed at the last minute from British release prints, the brief glimpse of

nudity before Milly’s demise was designed to help bookings of the film on the

Continent, with Powell’s pre-release claim that he found both nudity and Continental

versions of British films “boring” conveniently forgotten.

The film was increasingly booked as an adults-only engagement, and under these terms, Reading lifted its ban on the film for non-circuit bookings in July. During the hot summer when attendance usually fell, Kine Weekly noted that Peeping Tom continued to bring in crowds at the Gala Royal and in “suburban and provincial halls.” By late summer, trade sources noted that the film was “playing to very large audiences all over the country." It was approved for adults-only exhibition in Ireland, and Josh Billings could proclaim that “Critics threw the book at Peeping Tom, [but the Gala Royal and other

Jacey and provincial cinemas] threw the book back.” However, AIP, Anglo’s Americanpartner, passed on the film, and its U.S. release was handled by Gala-like artcinema/exploitation distributor Astor Pictures, who booked it into a range of supporting engagements in American drive-ins, inner-city theaters, and early adopters of the adults-only admissions policy.

The film was increasingly booked as an adults-only engagement, and under these terms, Reading lifted its ban on the film for non-circuit bookings in July. During the hot summer when attendance usually fell, Kine Weekly noted that Peeping Tom continued to bring in crowds at the Gala Royal and in “suburban and provincial halls.” By late summer, trade sources noted that the film was “playing to very large audiences all over the country." It was approved for adults-only exhibition in Ireland, and Josh Billings could proclaim that “Critics threw the book at Peeping Tom, [but the Gala Royal and other

Jacey and provincial cinemas] threw the book back.” However, AIP, Anglo’s Americanpartner, passed on the film, and its U.S. release was handled by Gala-like artcinema/exploitation distributor Astor Pictures, who booked it into a range of supporting engagements in American drive-ins, inner-city theaters, and early adopters of the adults-only admissions policy.

The case of Peeping

Tom illustrates the centrality of distribution and exhibition to the

production and reception of bold and experimental commercial cinema. Powell’s

film has been called an “independent” production, but it was independent only

of former partner Pressburger and the powerful Rank interests that had

sustained the pair for a decade. In 1959-60, Peeping Tom was very much a

product of its financier/distributor Anglo Amalgamated and the exhibition

environment in which they were operating.

Powell would have been acutely aware of this environment and committed to success within it, since the first of the five points in the Archers’ 1942 manifesto read, “We owe allegiance to nobody except the financial interests

which provide our money; and, to them, the sole responsibility of ensuring them

a profit, not a loss." Contrary to received wisdom, Powell appears to have met this responsibility

with Peeping Tom. The commercially-driven conventions within which Powell and screenwriter Leo Marks were working in 1959 enabled, not debilitated, their creation of the bold striations of style and tone in Peeping Tom. The film grew out of rather than opposed important trends in the movie business of the

time, most notably in distribution and exhibition. Further, the critical

outrage which greeted the film was as much a result of its confounding

categories between the prestige film, the circuit release, and the program

feature for provincial halls as it was of the actual licentiousness and mayhem

on display. In short, the same features which resulted in the film’s lamented

and lambasted commercial success in 1960 later led to its valorization as a

masterpiece of modernist cinema and one of the most influential films ever made.

* Kamera was by far the most sophisticated and artistically ambitious British glamour magazine of the late 1950s. Its pages featured Pamela and an

extraordinary group of models in Marks’ exquisite photo layouts which were

designed by Green, herself an accomplished writer, artist, photographer, and designer. Green passed away in 2010, but in her retirement years on the Isle of Wight, she presided over an incredibly detailed, profusely illustrated, and well-written website and blog, “Never Knowingly Overdressed,” in which she recounted her career with Marks and Kamera magazine. Her lengthy account of Peeping Tom's casting, shooting, and hostile reception is essential reading.

This essay is part of a much longer and more detailed consideration of the role distribution plays in the changing horror film which appears in A Companion to the Horror Film, edited by Harry M. Behshoff (2014), published by Wiley-Blackwell. I owe many thanks to Harry and to Julian Petley for their excellent feedback on several earlier drafts of this piece. An Amazon link to the book can be found in my previous blog entry on Kim Ji-Woon's A Tale of Two Sisters. Here are links to other sources on Powell, British cinema, Peeping Tom, Pamela Green and Kamera, and postwar American and British horror films.

Watch Live Hong Kong TV Channel

ReplyDeleteClick Here To Live

Watch Live TV Channels Online Broadcast On The Internet

livetvchannels.net

Live TV channels World Wide Internet TV watch free online TV broadcasts live The best live streaming guide of TV channels broadcast from around the world on the Internet for free.

Live TV channels